July 23, 2019

Here's Something Neat That You Don't see Everyday

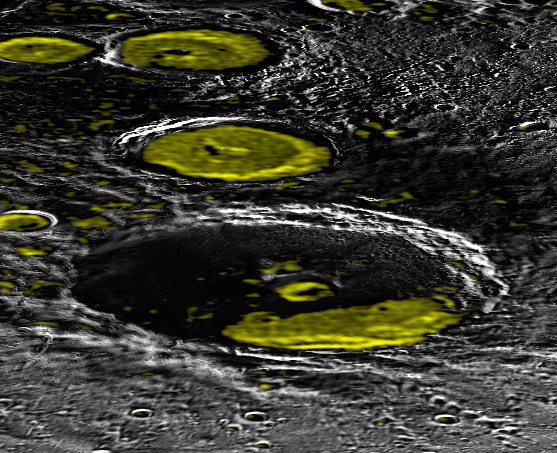

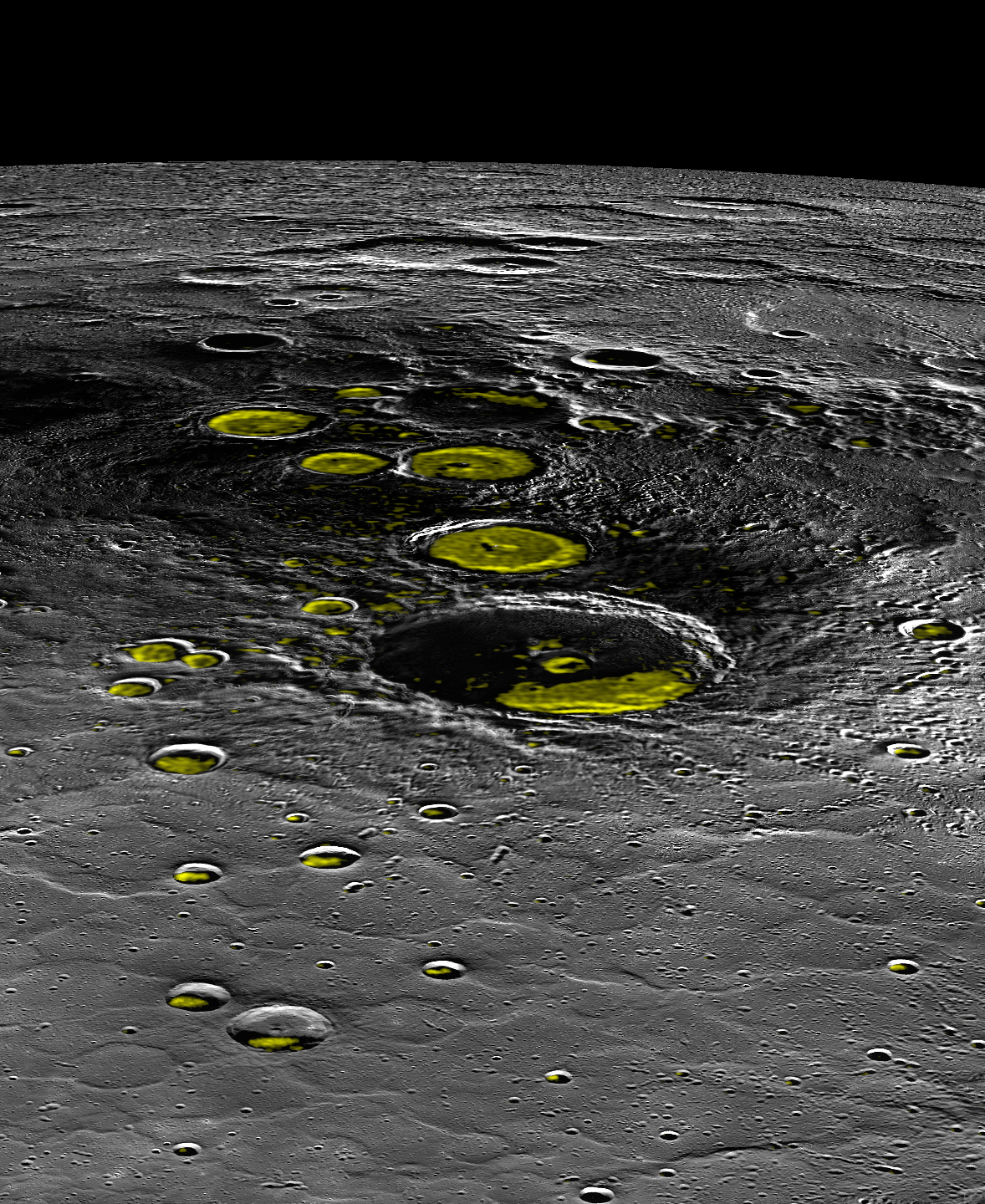

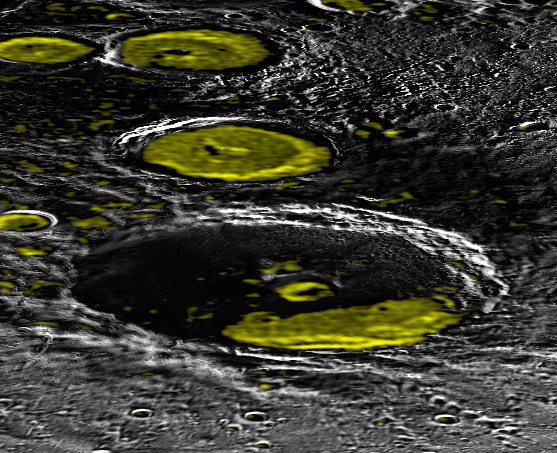

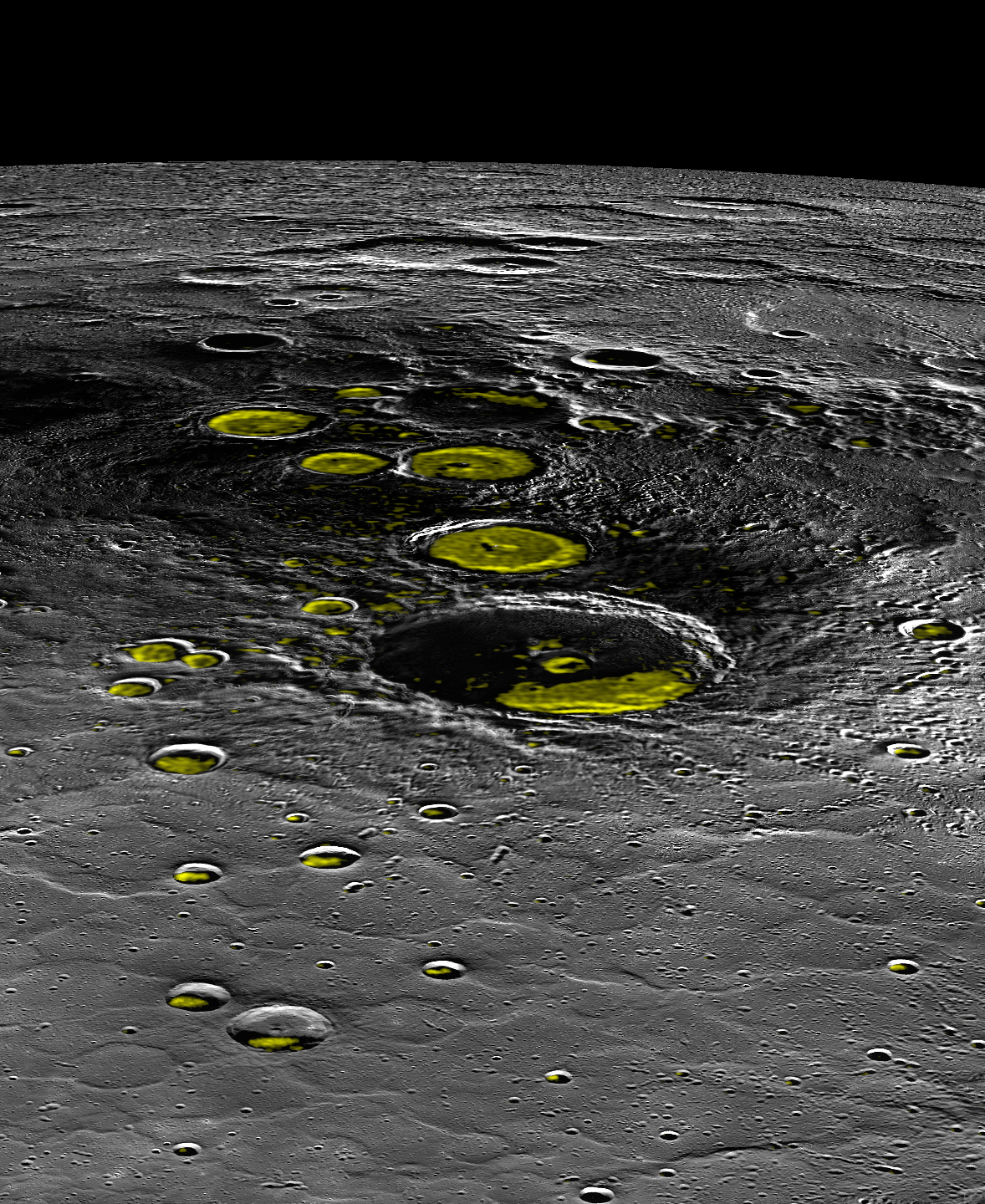

Here we have a false color image of...something.

Guess what the 'greenish-yellow' stuff is.

Is it :

A: Impact related lava flows in Lunar Craters?

B: Sand dunes in windswept craters on Mars?

C: Stromatolite colonies in brine pools in Australia?

Alas no.

It's even better than pancakes!

It's glaciers.

On Mercury!

The pictures of the Mercurian arctic were taken by N.A.S.A's Messenger spacecraft before its demise. According to the phys-org article there was initially some considerable skepticism that they were what they appeared to be. However, Arecibo Observatory has now confirmed that these are big piles of ice; actual glaciers. There's no mention in the article what phases the ice is (presumably 1-4).

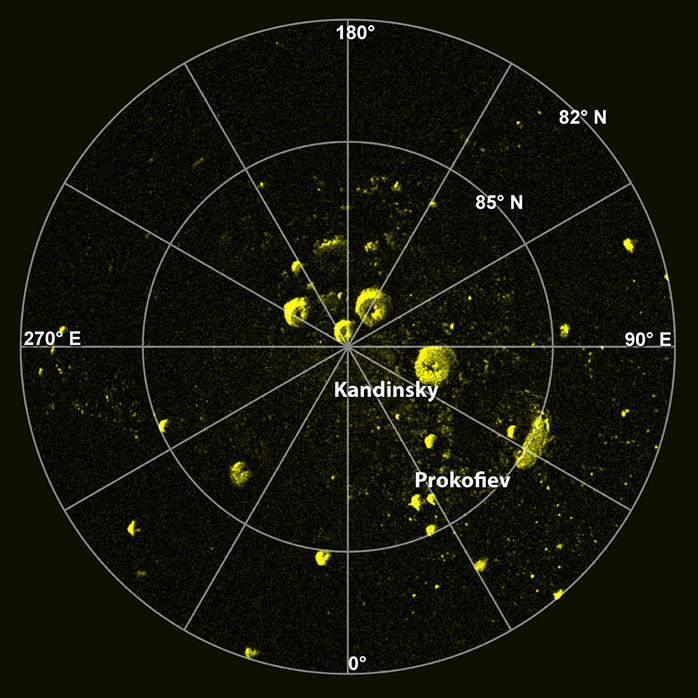

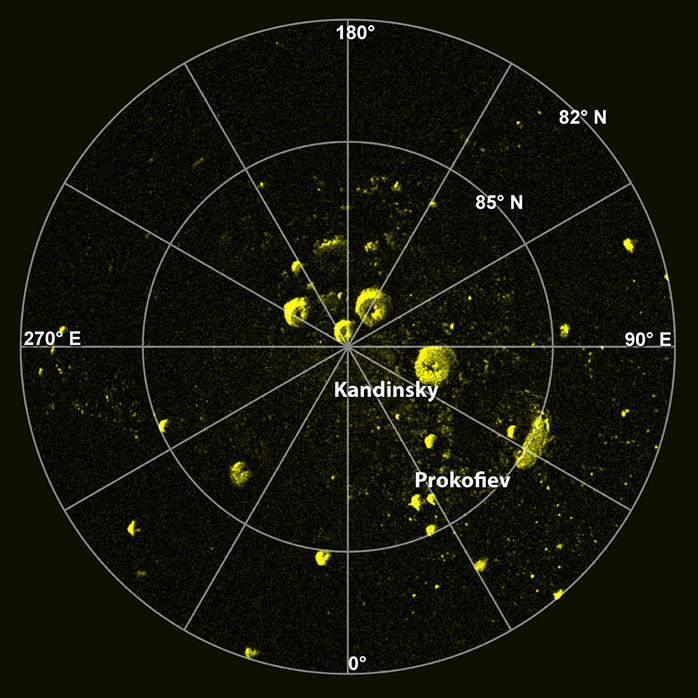

The sheer scale of the ice deposits is remarkable The big, half filled crater in the foreground, Prokofiev, is 69 miles across. Just eyeballing it, the nearly full craters, behind it, Kandinsky, Tolkien, Tryggvadottir, and Chesterton, are about 20 to 40 miles across. If Tolkien has a radius of 15 miles, then π r2 gives us a bit less than 707 square miles of ice for that smallish crater alone. How many cubic miles depends , of course, on the thickness, but that's a hell of a lot of ice. and remember, that's just one crater, and that's just the glacier, not the buried frozen mud and such.

What's remarkable is how far from the north pole the ice deposits seem to extend. They seem to exist south of the arctic circle. Presumably these are DEEP craters.

Now, one might ask, if Mercury (which is right next to the fricking sun and is hot enough to melt lead in its tropics) has actual glaciers, why doesn't the moon, which is much farther away have such spectacular ice deposits?

About that.

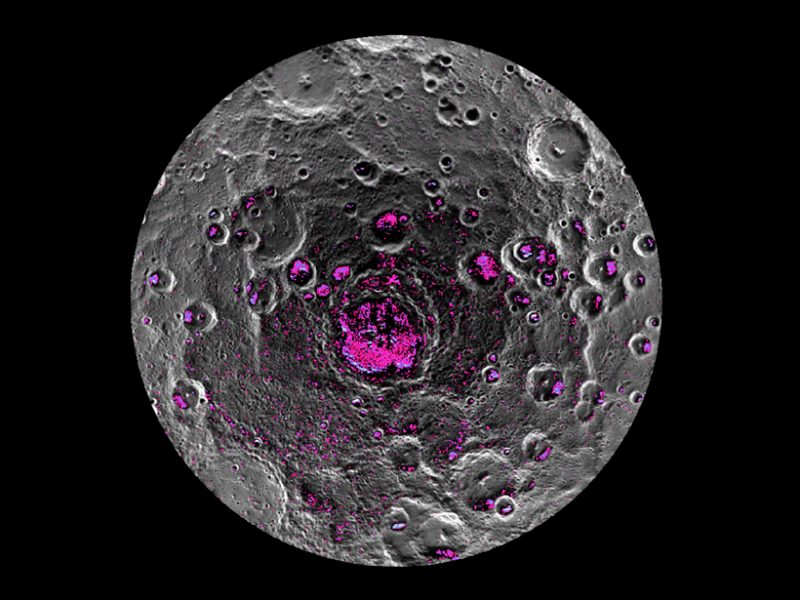

Indications of water had been detected in craters on the Moon, and Scientists have long suspected that there are ice deposits in the shadowed craters of The Moon and Mercury, which have almost no axial tilt. Those polar craters, being in permanent shadow, are invisible from the ground here on Earth. However, while satellites passing over the lunar poles have detected indications of ice, they haven't actually looked down into the craters on the moon with the same instrument that Messenger used to get these pictures of Mercury. So they didn't confirm what form the ice is in. It was always assumed to be something akin to permafrost with a few frozen puddles and some ice sheets. . However, all the other data from the lunar craters is consistent with what's been seen on Mercury, so it looks like there's probably a similar situation there, meaning much more ice than previously thought, and possibly in glacial form. Heretofore, studies have focused on ways to "cook" water out of the regolith.Well, having GLACIERS would rather simplify matters.

"Ensign Skippy, fetch me the ice axe and a bucket."

Art by Kiichi

This means we need to get one of those particular cameras into lunar polar orbit to confirm this, and if this is true it has immense potential to facilitate lunar settlements.

Of course this also means that not only The Moon, but Mercury (of all places) are potentially much easier to settle. Mining in space to bring things to Earth does not make any economic sense normally, but Mercury is a likely mother load of heavy elements like tungsten, gold, platinum group metals, and radioactives. The PGMs in particular could potentially make mining operations on Mercury worthwhile in a few decades.

All that aside, I just find it transcendentally cool that there are actual glaciers on planet Mercury.

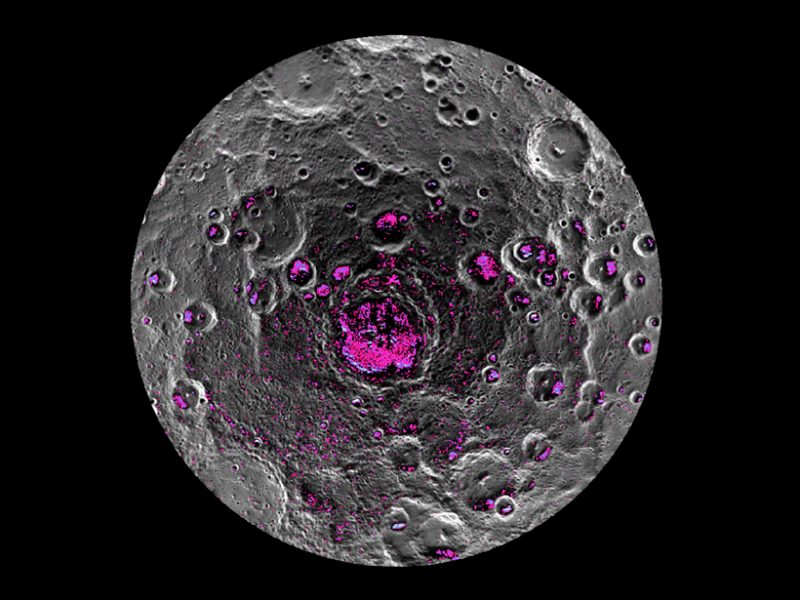

UPDATE: Antarctic too!

Note though, that this is not a direct radar photo like the one above; just an indication that there is ice and other radar reflective substances present. It's not clear what form they're in and it is certainly not a given that these deposits are the same sort of hectometer thick ice sheets seen in the above pictures of the northern glaciers, though it would seem likely that at least some are.

Guess what the 'greenish-yellow' stuff is.

A: Impact related lava flows in Lunar Craters?

B: Sand dunes in windswept craters on Mars?

C: Stromatolite colonies in brine pools in Australia?

Alas no.

It's even better than pancakes!

It's glaciers.

On Mercury!

The pictures of the Mercurian arctic were taken by N.A.S.A's Messenger spacecraft before its demise. According to the phys-org article there was initially some considerable skepticism that they were what they appeared to be. However, Arecibo Observatory has now confirmed that these are big piles of ice; actual glaciers. There's no mention in the article what phases the ice is (presumably 1-4).

The sheer scale of the ice deposits is remarkable The big, half filled crater in the foreground, Prokofiev, is 69 miles across. Just eyeballing it, the nearly full craters, behind it, Kandinsky, Tolkien, Tryggvadottir, and Chesterton, are about 20 to 40 miles across. If Tolkien has a radius of 15 miles, then π r2 gives us a bit less than 707 square miles of ice for that smallish crater alone. How many cubic miles depends , of course, on the thickness, but that's a hell of a lot of ice. and remember, that's just one crater, and that's just the glacier, not the buried frozen mud and such.

What's remarkable is how far from the north pole the ice deposits seem to extend. They seem to exist south of the arctic circle. Presumably these are DEEP craters.

Now, one might ask, if Mercury (which is right next to the fricking sun and is hot enough to melt lead in its tropics) has actual glaciers, why doesn't the moon, which is much farther away have such spectacular ice deposits?

About that.

A trio of researchers at the University of California has found evidence that suggests there is far more ice on the surface of the moon than has been thought. In their paper published in the journal Nature Geoscience, Lior Rubanenko, Jaahnavee Venkatraman and David Paige describe their study of similarities between ice on Mercury and shadowed regions on the moon and what they found.

Indications of water had been detected in craters on the Moon, and Scientists have long suspected that there are ice deposits in the shadowed craters of The Moon and Mercury, which have almost no axial tilt. Those polar craters, being in permanent shadow, are invisible from the ground here on Earth. However, while satellites passing over the lunar poles have detected indications of ice, they haven't actually looked down into the craters on the moon with the same instrument that Messenger used to get these pictures of Mercury. So they didn't confirm what form the ice is in. It was always assumed to be something akin to permafrost with a few frozen puddles and some ice sheets. . However, all the other data from the lunar craters is consistent with what's been seen on Mercury, so it looks like there's probably a similar situation there, meaning much more ice than previously thought, and possibly in glacial form. Heretofore, studies have focused on ways to "cook" water out of the regolith.Well, having GLACIERS would rather simplify matters.

This means we need to get one of those particular cameras into lunar polar orbit to confirm this, and if this is true it has immense potential to facilitate lunar settlements.

Of course this also means that not only The Moon, but Mercury (of all places) are potentially much easier to settle. Mining in space to bring things to Earth does not make any economic sense normally, but Mercury is a likely mother load of heavy elements like tungsten, gold, platinum group metals, and radioactives. The PGMs in particular could potentially make mining operations on Mercury worthwhile in a few decades.

All that aside, I just find it transcendentally cool that there are actual glaciers on planet Mercury.

UPDATE: Antarctic too!

These results support the observation that Mercury’s south pole has a substantially higher volume of frozen water ice and other volatiles than Mercury’s north pole

Note though, that this is not a direct radar photo like the one above; just an indication that there is ice and other radar reflective substances present. It's not clear what form they're in and it is certainly not a given that these deposits are the same sort of hectometer thick ice sheets seen in the above pictures of the northern glaciers, though it would seem likely that at least some are.

Posted by: The Brickmuppet at

08:46 PM

| Comments (10)

| Add Comment

Post contains 772 words, total size 7 kb.

1

Huh. Never really considered the existence of a Mercurial arctic.

Posted by: Pixy Misa at Tue Jul 23 21:33:05 2019 (PiXy!)

2

Mercury is one face to the sun, right?

Posted by: Mauser at Tue Jul 23 21:48:27 2019 (Ix1l6)

3

??? I thought Mercury wasn't tide-locked? How does this work? Is it constantly evaporating from the sun-facing side and condensing on the night side? According to the internet (grain-o-salt) mercury rotates 3 times for every two orbits about the sun.

Posted by: MadRocketSci at Tue Jul 23 21:56:42 2019 (K+Kza)

4

It was a minor plot point in some sci-fi game in my childhood that Mercurian miners would have to keep their equipment roving across the surface to avoid the sunrise.

Posted by: MadRocketSci at Tue Jul 23 21:58:04 2019 (K+Kza)

5

I guess the deep crater explanation is plausible if they're all above 90 deg latitude.

Posted by: MadRocketSci at Tue Jul 23 22:20:47 2019 (K+Kza)

6

Yeah, Mercury is in a 3:2 resonance, not tide-locked. So these are all at the north pole, where the crater walls are high enough to shield the ice from the Sun.

Posted by: Pixy Misa at Tue Jul 23 22:26:34 2019 (PiXy!)

7

Mercury is surprisingly hard to get to and I don't think anyone has yet landed a probe there. Quite apart from being close to the sun where it's hot, it's got a high speed orbit and no gravity to speak of to assist in a capture, and then once you do establish an orbit, the surface rotation is fast enough to become a serious consideration when you try and figure out a landing. Messenger did something like 9 gravity assists and took several years to get to Mercury.

Posted by: David at Wed Jul 24 01:20:14 2019 (7VRIY)

8

Indeed. However, once one is there it is easier to get back from than one would assume of something so far down the sun's gravity well. You see, its orbit is so fast that it acts like an additional rocket stage, so theoretically, mass drivers on Mercury could sent a constant stream of metals earthward without too much cost or difficulty once sufficient infrastructure had been built up.

Mercury is surprisingly hard to get to...

Indeed. However, once one is there it is easier to get back from than one would assume of something so far down the sun's gravity well. You see, its orbit is so fast that it acts like an additional rocket stage, so theoretically, mass drivers on Mercury could sent a constant stream of metals earthward without too much cost or difficulty once sufficient infrastructure had been built up.

Posted by: The Brickmuppet at Wed Jul 24 06:14:30 2019 (YUAc9)

Posted by: The Brickmuppet at Thu Jul 25 05:35:11 2019 (YUAc9)

10

Heh.

Posted by: Pixy Misa at Thu Jul 25 22:57:14 2019 (PiXy!)

38kb generated in CPU 0.0225, elapsed 0.1125 seconds.

71 queries taking 0.1004 seconds, 283 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.

71 queries taking 0.1004 seconds, 283 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.